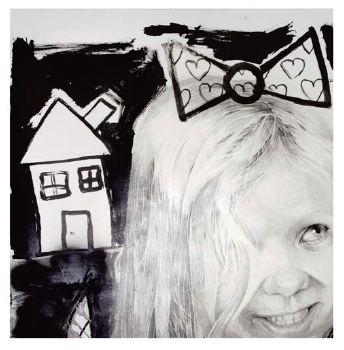

Jérôme Zonder, Poussière de Guignol

© Galerie Eva Hober

Seizing on strong iconographic symbols taken from the Nazi aesthetics and the worlds of childhood and cartoons, Zonder revisits these forms of narration and the innocence they carry (children drawings, clear lines) as well as the cruelty (realism, caricature) through mise-en-scenes with a gory tone where sex and barbarity are more than compatible.

Before freely mixing all these modes of expression, Zonder took his time to sharpen them one by one, exploring their logic of representation, their intentional strength and their power of suggestion. For the artist, the narrative processes are, above all, tools of creative effects rather than story supports, they are like “special effects” in a film, and can trigger breathtaking impressions of reality.

One of the resorts of the drawings lies in the collision of antinomic worlds, and the pursuit of graphic dissonance, both of which causing visual clashes. This opposition of contraries crystallizes in the characters of predator children that he stages. Naivety and bestiality coincide, and predator children represent an im- possible space where extremes collide. An impossible world that every culture has been able to represent with images to distance itself from it, and redefine itself at the same time within the reassuring contours of its identity. Predator children are the product of some logic of representation similar to the one that once led the Greeks to mount the torso of a man onto the hindquarters of a horse. Is comparing the image of the Centaurus, lecherous and violent, with that of a predator child going too far? Not if, beyond the cultural relativism that en- rolls them in conceptual schemes that are not comparable, these creations are perceived as figures which give shape to monstrous things thanks to an un- precedented collage.

Zonder organises the exhibition space in a theatrical disposal that is based around a hopscotch drawn on the floor. Besides, he explicitly engraves this work in a universal context of entertainment and masquerade which goes through the preliminary marking of an imaginary territory. A child will say “truce” or “it doesn’t count” and civilizations punctuate their calendar with celebrations to in- terrupt the “world order” and oppose it to “the effervescence of the celebration”1, planning carnivals where the transgression of social codes and the ending of taboos are officially authorized. On the scale of their specific spaces, children myths, popular celebrations and games set the rules that control and allow these experiences of radical otherness – one’s confrontation to barbarity, madness or death.

Zonder transposes these extreme experiences in the symbolic drawing space. He explores the limits of a graphic language, the point where he topples over and alienates himself in a polymorphic tale. Thanks to a principle similar to the hop- scotch one, he jumps from one symbolic space to another and tests its boundaries. The “sky” describes this symbolic jump once more. It is a symbolic jump where Zonder moves around, in an obstinate attempt to concentrate, in one sin- gle vision, the sum of the worlds that make us, both physical and symbolic worlds. The “sky” pole of the hopscotch comes with the only abstract drawing of the exhibition. It is exclusively made up of circles of various scales as he ex- pends a complex graphic network that constitute for Zonder a matrix for his plastic research, in which appears the germ of the themes of connection, net- work and shortcut, of transformation and the pursuit of limits, all of which will be found in his each of his drawings.

At the other pole of the hopscotch, a “black drawing”, drawn with a pencil on a sheet covered in Indian ink, depicts a corpse. This black drawing with a black background banks on the notion of the non-depictable and invokes this imagi- nary mechanism that consists in the act of fantasizing images. They are the im- ages of our own fears that nourished the “fear of the darkness” of our childhood. When reviewed through the prism of fear and paranoia, Zonder’s drawings ap- pear as fantastic semiological devices where the attempt at developing a sci- entific, political, educational or religious discourse is parodied in a big way and confronted with the hopelessness of the unknown.

Beyond the violence of the subjects he deals with, the disturbing nature of Zon- der’s pieces comes mostly from his cold and powerful mastery of processes of graphic representations. He knowingly botches these processes to build a lan- guage that tells its powerlessness to build this Great Story of the world that ide- ologies desire so much.

1 Roger Caillois, l’homme et le sacré, p.129, ed. Folio Essai.

Marguerite PILVEN, November 2009.